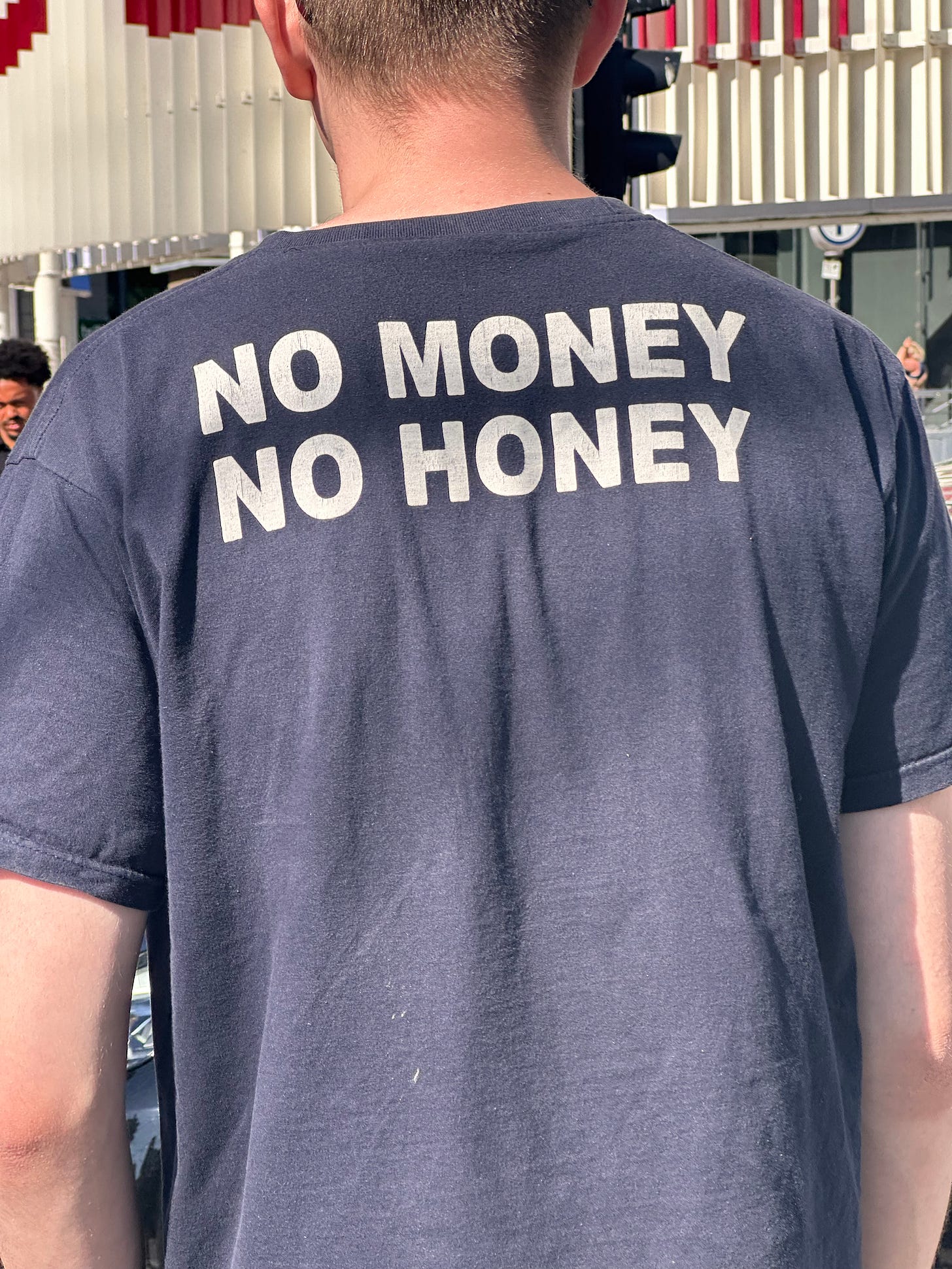

My husband didn’t pay for my drinks on our first date. He didn’t even do the fake reach for his wallet. It didn’t necessarily bother me, but of course, I did notice. In the U.S., men paying the bill on the first date is more often than not, a heteronormative given1. But at that point, I knew that dating internationally was a different ball game; home rules didn’t always apply. Besides, I long considered myself a feminist and wore my indifference on these matters like a badge of honor. I didn’t realize, however, that by falling for my Norwegian Prince, I was saying goodbye to the Princess treatment for good.

Now, I’m not trying to call Benjamin out. He is the kindest man I’ve ever been with —hence the marriage. But somewhere along the way from that date to our wedding, it dawned on me that this was the first relationship in which I was seen and treated as an equal. As it turns out, that feels much different than simply talking about it. Throughout my life, I’ve dated men from so many different backgrounds, you would be forgiven for assuming it was intentionally anthropological. So now, armed with my vast qualitative research and the clarity of hindsight, I can’t help but hypothesize that the genuine equality I feel with Benjamin is, at least in part, a product of the egalitarian Norwegian culture he grew within.

Since moving here, I’ve grown accustomed to the Norwegian way. I’m no longer surprised by the Norwegian women in my office who gently scoff at the British or Spanish men who make grand gestures of holding doors open for them. The gangs of young fathers pushing strollers on their morning pappapermisjon2 strolls now go virtually unnoticed. And I’ve come to understand that paying for women on dates is often seen as infantilizing3. In fact, in many of the couples I know well enough to ask, the women tend to earn more than their partners. All masculinity seems intact and I no longer feel the urge to be proud of them for navigating the imbalance gracefully.

Of course, I’m wary of painting the whole of Norway as some fully realized feminist utopia. Relics of the past linger4, there are regional differences, and the wage gap persists5. But what I see in my peers — young professionals in the capitol city, mind you — leads me to believe that at least on an interpersonal level, the patterns and practicalities that make up relationship dynamics are far less gendered than what we see in most of the world.

Let’s stick to first date norms, for example. The Social Guidebook to Norway6, cheekily encourages men who are new to Norway’s infamously casual dating scene to:

Be a gentleman just like Norwegian women like it. Do not pay for her.

Do not prepare anything too special. Do not put in more effort than she does. Simply make her feel like you both are equal. And that she is free to leave at any moment!

While this advice may initially read as an Incel’s embittered dating strategy, it seems to be surprisingly accurate advice for wooing the fiercely independent and practical women of Norway. Marina, the Russian-Canadian content creator behind Dating Beyond Borders7, often focuses on this topic in the “man on the street” style interviews she conducts around the world. In a long-form follow up interview8 with Sondre, one such man Marina met in Oslo, he confirms this:

Let’s say that you’re doing lunch in a low maintenance, cozy Italian or something. And then the question comes up: who’s taking the bill? Usually, it will be split, or it will be, ‘I’ll take the next one’. Somebody will offer to do that because that opens up the door for, Okay, this was a success, this was pleasurable. I would like to do this again. Then you give the other date person the chance to say, “Actually, I’ll pay for it myself,” because that way the person can, in a firm but not direct way, say, “this was not for me. I don’t feel like owing you anything”.

Now, this may seem like a minute detail in the bigger picture of a couple’s story. But if you’ve dated in the U.S., or anywhere outside of northern Europe, really, you know that even in 2024, this one small gesture can still stop many women in their tracks. Whether you call it chivalry or admit that it’s a sign of a man’s “provider mindset”9, that’s on you. In contrast, Sondre explains that:

Growing up as a Norwegian, you learn that self-sufficiency is a great value in a person and you also want that in a romantic partner because again, there's the word – partner. I don't want to be responsible for you. You're a grown ass adult. Get a hold of yourself.

Okay, go off! This ideal of self-sufficiency is not only at the crux of Norwegian gender dynamics, it seems to be central to Norwegian identity — no matter where you sit on the gender spectrum. Broadly speaking, Norwegian culture highly values practicality, modesty, and independence. And self-sufficiency is a sort of lovechild of all three. For ages, the harsh environment and their tumultuous sociopolitical history has forged these qualities in Norwegians; their view on gender roles have then been shaped by all of this, as well. Gender equality is quite practical, after all.

Of course, this mentality is not only seen on the first date. The rumors are true: Norwegian men often take just as much time off to care for newborns as their partners do; the government allows for “49 weeks (15 weeks are reserved for each parent) with 100% income coverage or 59 weeks (19 weeks are reserved for each parent) with 80% income coverage”10. And while there’s still room for improvement, Norway is ahead of the curve when it comes to the gendered divide of time spent on household work11.

From paying the dinner bill, to taking care of the home and raising a family, the largely gender-neutral way Norwegians view the responsibilities in their relationships is not just a personal preference, there has been a concerted effort to codify it since the 1970’s. And sadly unlike the U.S., these laws and the societal views they impact have only strengthened over time.

I love all of that, don’t get me wrong. It’s what so many of us claim to fight for, both in our political discourse and personal relationships. But if I’m being honest, I’ve found that there is a part of me that misses some aspects of the traditional roles I grew up watching and mindlessly reproducing. Much to my own horror, I assure you! I’m thrilled that Benjamin and I share our household responsibilities equally, I have a true partner that I can count on — not to “help” me, but to take care of things of his own volition. But if he didn’t come into my life and force Norwegian values on me, I’d likely still be the one doing the good ole fake reach for my wallet on first dates with men who would never let me pay, but also never learned to clean a toilet.

Although my highest self is begging me not to, I can acknowledge that my most primitive desire is to have the best of both worlds. I, too, am a product of the environment I grew up within. My monkey brain still tells me that Big Strong Man does hard, gross task. I want to be strong until the firewood needs to be carried inside. I want to be independent until the bill comes. Can’t I be treated as an equal until I want to be treated as a helpless Princess who needs protection? And financing?

Apparently, I’m not alone in this low-vibrational instinct. In his article on the topic, Santul Nerkar studied a sample of Gen Z singles in the U.S., finding that personal views on gender norms didn’t impact this expectation much at all, “on average, both men and women in the sample expected the man to pay [on first dates], whether they had more traditional views of gender roles or more progressive ones.”12 And if Gen Z still think this way, what hope do the rest of us Americans have?

It's called chivalry! I can hear you thinking loudly.

These are just basic manners! I heard you, I heard you.

But let’s not forget, chivalry is founded in the idea that women are inherently weaker and require a man’s aid or protection in order to function day-to-day. The eleventh-century epic poem, The Song of Roland, outlined the code of chivalry essentially because knights had become so violent and prone to rape, the church had to create a code of honor13. Do we still want anything to do with a culture based in those standards? Nerkar goes on to reason that:

the persistent tradition of men paying for women might seem like a harmless artifact. But in a relationship, such acts don’t exist in a vacuum. Psychologists differentiate between two forms of sexism: ‘hostile sexism,’ defined by beliefs like women are inferior to men, and ‘benevolent sexism,’ defined by beliefs like it is men’s duty to protect women. But the latter can give way to the former.

These behaviors are only indicators of genuine politeness if they’re extended to everyone because of their shared humanity, not just to women. Unless he’s offering to pay the tab at the bar with his best mate, or holds the door open for his male colleagues, too — that’s not just good manners, babes — there’s a gendered social contract being written and your complicity signs it on the dotted line.

Look, cultural norms persist because that’s where we all feel safest. We reproduce what we see, what we know, and what we believe works — even imperfectly. So I’m not trying to critique anyone’s lifestyle. I’m merely contemplating the double standard that too many women, myself included, have gotten away with enjoying for too long. And while it’s certainly not solely our responsibility to change the system, we can put an end to our own interpersonal inequality. If we want to.

Because I don’t think we can demand gender equality and still bask in the preferential treatment of benevolent sexism. In this case, two things cannot be true at the same time; the complexity of this particular duality renders it untenable. It doesn’t feel like feminism, and it sure as hell ain’t equality. It’s all too easy to relax into the comfort of a kept lifestyle while convincing yourself that you’re on equal footing. But sexism that benefits you is still sexism.

Benjamin does carry the firewood up from the basement. But we take turns, depending on who notices we need a refill. Because much to my chagrin, I am physically capable of doing it, too. And I’m not saying he never pays for dinner. It’s just that he only pays the full bill when it’s his night to cook and he can’t be bothered14. Not because it’s his responsibility as a man.

I thought I was a feminist before I met my husband. Ideologically, at least. In reality, I don’t think I ever really wanted the daily grind of true equality until I felt it all for myself. Being pampered in the passenger seat was easier, more comfortable, sure. Even if it came with subconscious belittlement, it was all I knew. However, the heavy loads of firewood are nothing compared to the unfathomable lightness of being seen as a whole, empowered person. It has fully freed me from whatever invisible tethers I was born into as an American woman.

Trust me, it feels unnatural to admit that this shift in perspective was ignited in me by a man. Gross. But that’s the power of cultural conditioning. As much as the little Princess within me might contest, I’ve never needed a knight in shining armor to save me from the harsh realities of this world. All I need is a hot bestie with whom I share the responsibilities of life. And that is something I definitely have.

Despite being on the smaller end of the global scale of inequity: Exploring Norway’s Fertility, Work, and Family Policy Trends

Special occasions not included

This really gave me a lot to think about! I am a bit critical of Norwegian’s claim to gender equality—I still have trouble with men speaking over me or asking me to grab their coffee in the office, and conversations about consent/sexual assault (and legal protections for sexual assault!) feel much further behind to me than I was used to in the U.S.. But the absence of benevolent sexism really could point to a much more holistic understanding of gender equality in social dynamics.